By 2030, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is expected to make appropriate antibiotics harder to access for many patients in India, mainly by reducing the effectiveness of older drugs and increasing pressure and shortages for newer, last‑line agents, unless current policies are fully implemented.��

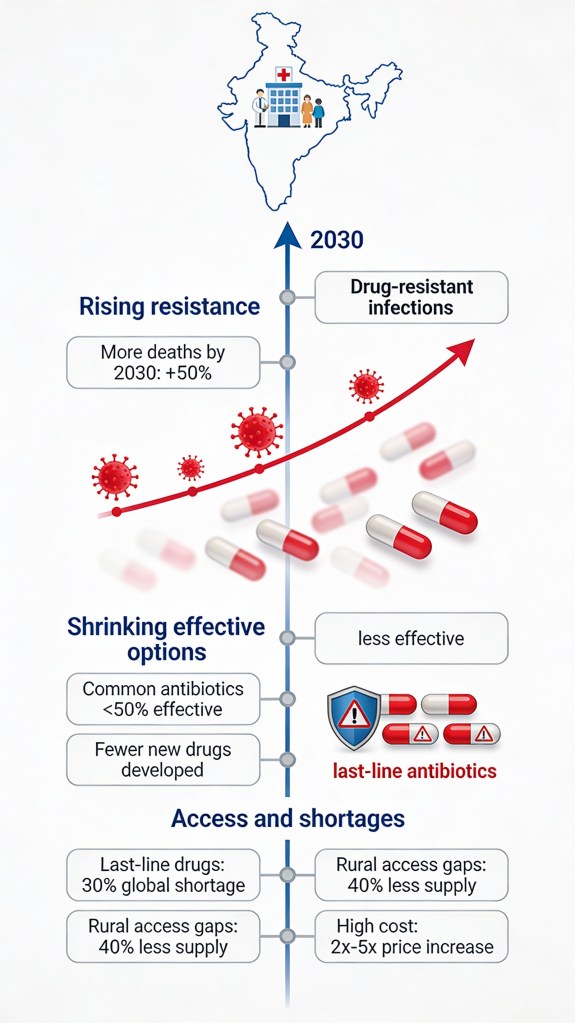

What projections say up to 2030 Burden models for India forecast that, without stronger action, deaths associated with AMR could rise steeply by 2030, reflecting many patients not getting an effective antibiotic in time.�

Global and LMIC‑focused analyses warn that shortages of quality‑assured antibiotics will become a bigger concern toward 2030, especially in low‑ and middle‑income countries struggling with procurement and supply chains like India.��

How AMR affects availability, not just resistance As resistance grows, routine first‑line antibiotics stop working, forcing clinicians to use a narrower set of expensive or reserve drugs, which increases risk of stockouts for those specific antibiotics.��

Shortages and interrupted supply then drive more inappropriate use of whatever is available (often broad‑spectrum or sub‑optimal drugs), which further accelerates AMR and creates a vicious cycle of reduced effective options.��

India’s policy path to 2030. India’s National Action Plan on AMR (first version 2017–2021 and NAP‑AMR 2.0 for 2025–2029) aims to slow AMR and protect antibiotic availability through stewardship, better surveillance, infection prevention, and investments in R&D and access.��

The updated plan explicitly strengthens diagnostic networks, AMR labs, and antibiotic stewardship and seeks tighter control of irrational and over‑the‑counter antibiotic use, which is essential to keep key antibiotics effective and worth manufacturing.��

Expected risks if implementation is weak If enforcement of prescription rules, OTC bans, and stewardship stays patchy, India will likely remain a hotspot where many older antibiotics are ineffective, while access to newer and reserve drugs remains limited to richer patients and big hospitals.��

Inefficient procurement, slow registration, and weak public financing—already major reasons for antibiotic shortages in low‑ and middle‑income countries—are projected to keep denying many Indians appropriate antibiotics by 2030 unless governance improves.��

Potential improvements with strong investment Economic modelling suggests that sustained investment in AMR control and access to innovative antibiotics could yield very high health and economic returns for India by 2050, implying that strengthened supply and access systems in the 2020s (including up to 2030) are both feasible and beneficial.�

Expanding local manufacturing, fast‑tracking needed antibiotics, and integrating AMR goals into universal health coverage could, by 2030, reduce inequities so that effective antibiotics are available and affordable beyond just metro tertiary hospitals.��

Leave a comment